The Japanese Watch Brands Leading The Industry In 2024

From names you know to ones you probably don’t, we take a look at whose making what in the Land of the Rising Sun.

From the outside, it would seem as though watchmaking in Japan can be split into two distinct camps. On one side are the global names such as Seiko, Citizen, and Casio who can chock out 30m quartz movements a second; the other is the independents, usually single watchmakers whose output is in the single digits and where every component is made by hand.

However, that arbitrary delineation overlooks the Japanese qualities, such as attention to detail, pursuit of excellence and obsession with accuracy that lie at the heart of every watch producer in this seemingly disparate land.

Leading Japanese watch brands

There are three major names that dominate the watch industry in Japan: Seiko, Citizen and Casio. They have various subsidiaries, brands within brands, and cover every price point from pocket money to wallet destroying.

Seiko

It all started in Tokyo in 1881 with a man called Kintarō Hattori, who opened a shop capitalising on the burgeoning interest in Western timepieces by becoming an import business, making his name by stocking brands that were exclusive to him.

His next step was to start his own brand called Seikosha – which roughly translates as ‘House of Exquisite Workmanship’ – eventually changing it to Seiko in 1924. By 1912, Seikosha had produced the first Japanese wristwatch, the Laurel, but it was Hattori’s grandson Shoji who really put the brand on the map.

He engineered Seiko into being the official timekeeper of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and he was at the helm when Seiko launched the Astron – the world’s first ever quartz watch. Or to give it its other title, Destroyer of the Swiss Watch Industry, seeing as its launch sparked an appetite for cheaper, more accurate quartz over expensive mechanics.

Seiko’s other ground-breaking invention is the Spring Drive. A movement that mostly mechanical but has a quartz oscillator, so you get all the romance of a mechanical watch with the accuracy of quartz.

Grand Seiko

This once-insider subsidiary of Seiko is the result of Seiko’s desire to create the idea timepiece – one that would be durable, pared-back and with chronometric standards that would surpass any Swiss watches.

The first-ever Grand Seiko was launched in 1960. However, in a wonderfully ironic twist, production was pulled in 1975 because quartz had destroyed any demand for mechanical watches. Luckily for watch geeks everywhere, manufacturing resumed in 1998.

Despite the seeming austerity of Grand Seiko’s designs, there is a romance there. The textures of the dials are inspired by birch bark, or the way snow settles on the mountains in Taisetsu, the 21st of Japan’s 24 ‘sekki’, or seasons.

Credor

Still keeping it in the Seiko family, this brand was first launched in 1974 and was a place where Seiko’s traditional craftsmanship could be combined with its high-end technological innovations.

This is the most Japanese of Seiko’s offshoots. The designs are all interpretations of Japanese culture, rather than being influenced by trends or the tastes of other markets.

The pinnacle is the Eichi. Made by elite watchmakers, it has hand-painted indices and a porcelain dial whose particular shade recalls the snowy landscapes of winter in the mountainous region of Shiojiri in the Nagaon Prefecture, where the studio is based. And, in a next level move, the hands and case-back screws are all blued by hand by a single craftsman.

Orient

Part of the Seiko Group but not involved in any way with Seiko Watch Corporation – it’s owned by printer company Epson – Orient first started in 1901 as the eponymous imported watch business of Shogoro Yoshida, who eventually moved into watchmaking in 1934.

In 1967 it had developed the world’s thinnest automatic and, after Epson secured a 52% share of the business in 2001, it opened its Technical Centre 2003 to develop high-precision calibres.

It has a reputation for producing reasonably accurate watches, using in-house movements, at decent prices and also for making boldly designed timepieces. Its multi-year rainbow calendar being a particular highlight.

Casio

The Kashios, Casio’s founding family, started life in extreme poverty. But it was a calculator that made their fortunes. The Casio 14-A to be precise. Launched in 1957, it was a prize-winning success, but it was the 14-B that really got the brand off the ground. The addition of a square root calculation option saw 4,700% percent growth for the company.

By 1974, Casio was keen to expand into watches. However, no one would supply parts. So, Casio did everything itself, on a shoestring. That meant no moving parts, digital liquid crystal display, and a plastic case. The formula worked and, for a while, Casio was the largest producer of watches in Japan – a title it reacquired in 2015.

The success of the Casiotron, its first watch, was followed in 1984 by the G-Shock – a chunky hunk of plastic that, as the name suggest, was shockproof. Hot on the heels of this cult product was the Baby-G, a prettily coloured confection that ruled women’s wrists in the 1990s.

Now Casio’s stock in trade is collaborating with brands and artists to produce limited-edition G-Shocks with ever-spiralling price tags.

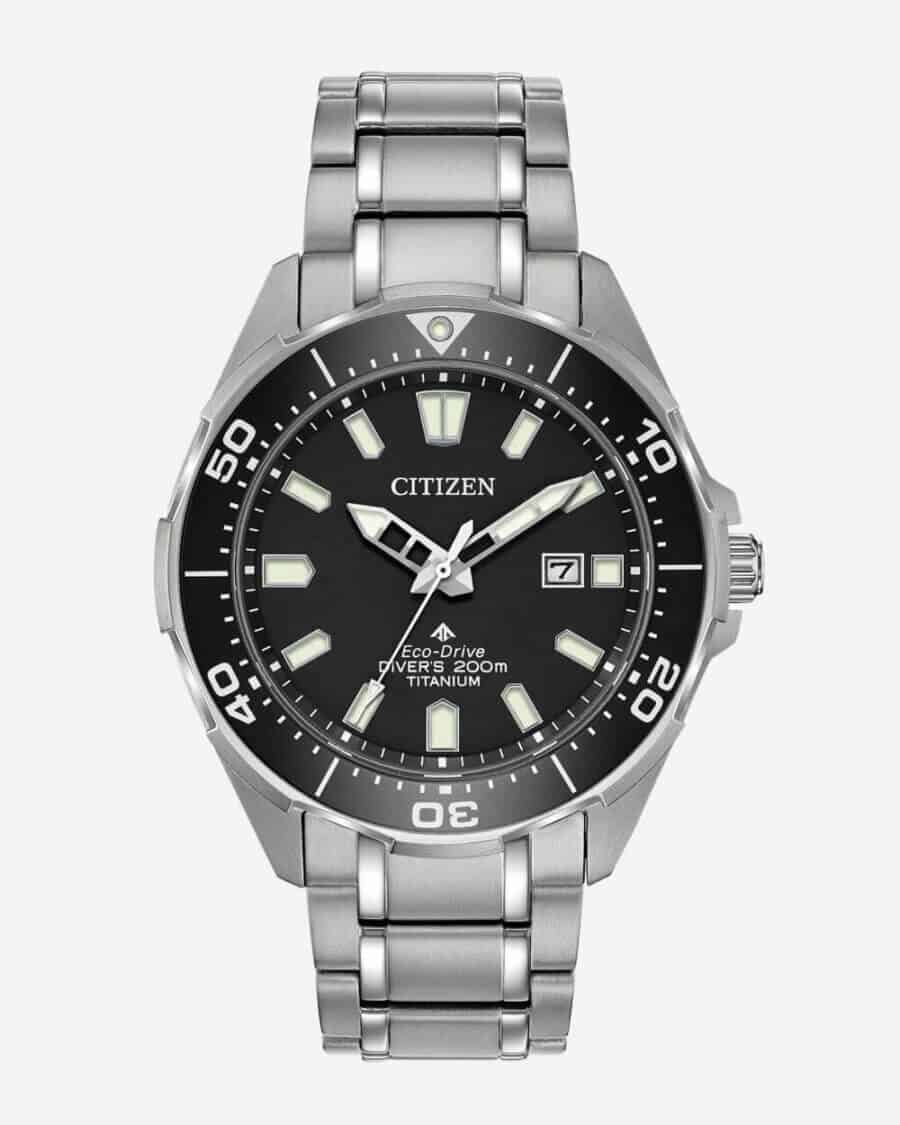

Citizen

This behemoth has its roots in a jewellery shop owned by Kamekichi Yamazaki, in 1918, who bought Swiss precision equipment to make his own movements. This venture was so successful that by 1927 he was able to transform his business into a watch company that was viable enough to be bought by businessman Yasaburo Nakajima and renamed Citizen.

Despite the US bombings during WWII, by 1960 Citizen had enough manufacturing capacity to be able to make movements for Bulova and other non-Swiss brands. Unlike Seiko, it bet on tuning fork technology so was a little slow on the quartz uptake, not producing a quartz-powered timepiece until 1974.

Citizen’s most important innovation has been the Eco Drive: a movement powered by a lithium-ion battery charged by solar cells. It has a power reserve measured in months and the battery never needs replacing.

Aside from movements supplied by the Citizen-owned, Swiss-based La Joux Perret, everything that goes into a Citizen watch is made in Japan. As a company it is obsessed with accuracy, which led to the creation of the Caliber 0100, a movement with an annual accuracy of ±1 second. Given the average decent quartz movement has a ± of 3 seconds, going up to ±15 for lower-end ones, it’s an impressive achievement.

Independent Japanese watch brands

With production quantities usually in single digits, these names might not be on your radar, but each is making a name for themselves in horology circles.

Hajime Asaoka

This product designer by trade taught himself watchmaking after being asked to design one for someone else. In 2009 he unveiled Japan’s first watch with an in-house tourbillon, one which was driven by a third wheel that has its pinion secured by ball bearings rather than synthetic ruby screws. His signature is an oversized balance wheel.

Minase

The brand was an insider secret until 2017 when it finally started distributing globally. It is defined by elaborate construction, meticulous finishing and a penchant for non-round cases. The movements are ETA, which isn’t a minus point really. If you can’t make your own, you might as well buy the best.

Masahiro Kikuno

This wunderkind taught himself how to make watches using George Daniels’ book Watchmaking, which he had to translate from English in order to follow it. His first watch was a wrist-sized version of a wadokei – the traditional Japanese timekeeper used during the Edo period before the Western method took over.

He does everything by hand, and he’s even handmade a tourbillon. No wonder he’s the youngest person ever to be admitted to the Académie Horlogère des Créateurs Indépendant (AHCI), the most prestigious collective of independent watchmakers in the world.

Naoya Hida

This eponymous brand was founded in 2018 with one principle: to make high-end watches of superlative quality in very limited numbers.

Hida was formerly a rep for F.P Journe, which is also where his mater watchmaker Kosuke Fujita is from, and it’s evident in the aesthetic. The watches are restrained, some bearing a resemblance to Patek Philippe’s Calatrava, and once a new batch is introduced the previous one is discontinued, making this brand cat nip for watch collectors.

Norifumi Seki

Purportedly the next big thing in watchmaking, this 24-year-old from Tokyo is the first-ever Asian to win the esteemed F.P. Journe Young Talent Competition with a superb pocket watch powered by an intriguing movement comprising elements cherry picked from tried-and-tested calibres – Valjoux 7750, Peseux 7040 – and components made from scratch.

No other watches as yet, but his Instagram will keep you posted on new developments.

A brief history of Japanese watchmaking

When the Portuguese missionaries arrived in Japan in the mid-1550s, it wasn’t just their red hair that fascinated the Japanese, it was also their mechanical clocks. Japanese scholars, upon analysing these timekeepers, decreed them utter rubbish because they divided day and night into equal length all year round.

For the Japanese, the day was defined as the interval between sunrise and sunset, and sunset to sunrise. Each of these intervals were subdivided into six ‘hours’, each of which corresponded to, on average, two Western hours. The actual duration of the Japanese hours would vary according to the seasons, with the maximum and minimum ‘hour’ values being reached at the solstices.

Basic Japanese clocks had to be set daily at sunrise, but more expensive ones, equipped with a foliot regulator and verge escapement, one for day and one for night, would only need adjusting every two weeks. This way of timekeeping was eventually abandoned following the Meiji Revolution of 1867, which saw Japan become rapidly industrialised and adopt Western ideas.