Mechanical Watches: Everything You Need To Know Before Buying One

If you’re looking to buy your first mechanical watch but not sure where to start, here’s a handy guide to movements, mechanics and mainsprings.

Let’s start by saying that no one needs a mechanical timepiece – one filled with gears, wheel, and cogs. Your mobile phone keeps better time, as does a quartz watch. But timekeeping accuracy isn’t why we continue to buy these seemingly retrogressive things. A mechanical watch is a signifier – of status, sartorial preferences, the person you really are.

There’s a reason the cast of Succession pair their tech bro gilets and logo-less baseball caps with IWCs, Vacheron Constantins and a steel Patek Philippe Nautilus rather than Apple watches. The latter says you can’t live without email; the rest are signs of wealth, privilege and taste.

If you’re looking to go analogue, here’s a handy primer on what to look for, what not to worry about and some timeless brands to get you started.

What is a mechanical watch?

Vacheron Constantin

A mechanical watch is the catch-all term for any watch not powered by a battery, but by kinetic energy. Under this umbrella term you have ‘automatic’: a timepiece with a rotor, which will either be a sizeable semi-circle, a small micro style, or a circle of material around the outside of the movement. This rotor moves when you do, and the movement of the rotor winds the mainspring.

The other type is manual, or hand, wound, where you use the crown to wind the mainspring. There are hybrids known as meca-quartz, usually used in chronographs where the movement is quartz, but the stopwatch functions are mechanical. However, the two distinctions to know about are automatic and manual wind.

How does a mechanical watch work?

The escapement on a mechanical Rolex watch

As the rotor moves (or as you wind the crown), the mainspring tightens, storing energy. This energy is then released through a series of gears to power the balance wheel. If the watch has a see-through caseback, you should be able to see the wheel oscillating backwards and forwards at a constant rate.

Each swing of the balance wheel releases a tooth on the escapement – a lever, which is attached to the centre of the balance wheel, that connects to a tiny toothed wheel. This locking and unlocking manages the release of power from the balance wheel and moving the gear train, which, in turn, allows the hands to advance. The “tick-tock” you hear is the escapement.

A quartz watch, by contrast, ticks due to a stopper motor, which moves the seconds hand once per second. This also gives the seconds hand on a quartz watch the jerking movement as opposed to the elegant sweep of a mechanical watch.

What is an in-house movement?

Zenith El Primero movement

Annoyingly, both the short and long answer to this amounts to “it depends on what you want”. Let’s start with ‘in house’, two words guaranteed to start an argument at a watch fair. Back in the 90s, no one really cared whether watch brands made their movements under their own rooves. Rolex was using Zenith’s movements in its Daytonas, IWC and Breitling were taking Swatch Group’s ETAs, and Audemars Piguet was cadging off Jaeger-LeCoultre.

This was, of course, a hangover from the Quartz Crisis, when the Swiss watch industry was caught napping by Japanese watchmakers and suddenly all everyone wanted was cheap, battery-powered timepieces rather than expensive mechanical watches. After this dramatic slump, R&D on mechanical movements just wasn’t a sensible expenditure for most brands.

The likes of Rolex, Patek Philippe, Zenith and Jaeger-LeCoultre, who already had the infrastructure, never stopped making their own movements and even loaned them to others – Zenith’s iconic El Primero, for example, was used by Rolex, TAG Heuer and Panerai.

Jaeger-LeCoultre is one of the few watchmakers that create everything under one roof

In 2002, Nicholas Hayek Sr, then-CEO of Swatch Group, announced he no longer wanted ETA – the uber-movement supplier made up from the acquisitions of movement makers Valjoux, Peseux, and Lemania – to supply third parties. Suddenly brands were given the choice of relying on other movement makers, such as Sellita and Soprod, or doing it themselves. So ‘in house’ started to become a badge of honour; a sign that the brand was ‘doing things properly’.

But what ‘in house’ actually means depends on who you’re asking. The purists would argue that only those who have everything under one roof, such as Jaeger-LeCoultre or Zenith, are allowed to say their movements are in house, because the brand takes charge of every step from conception to assembly.

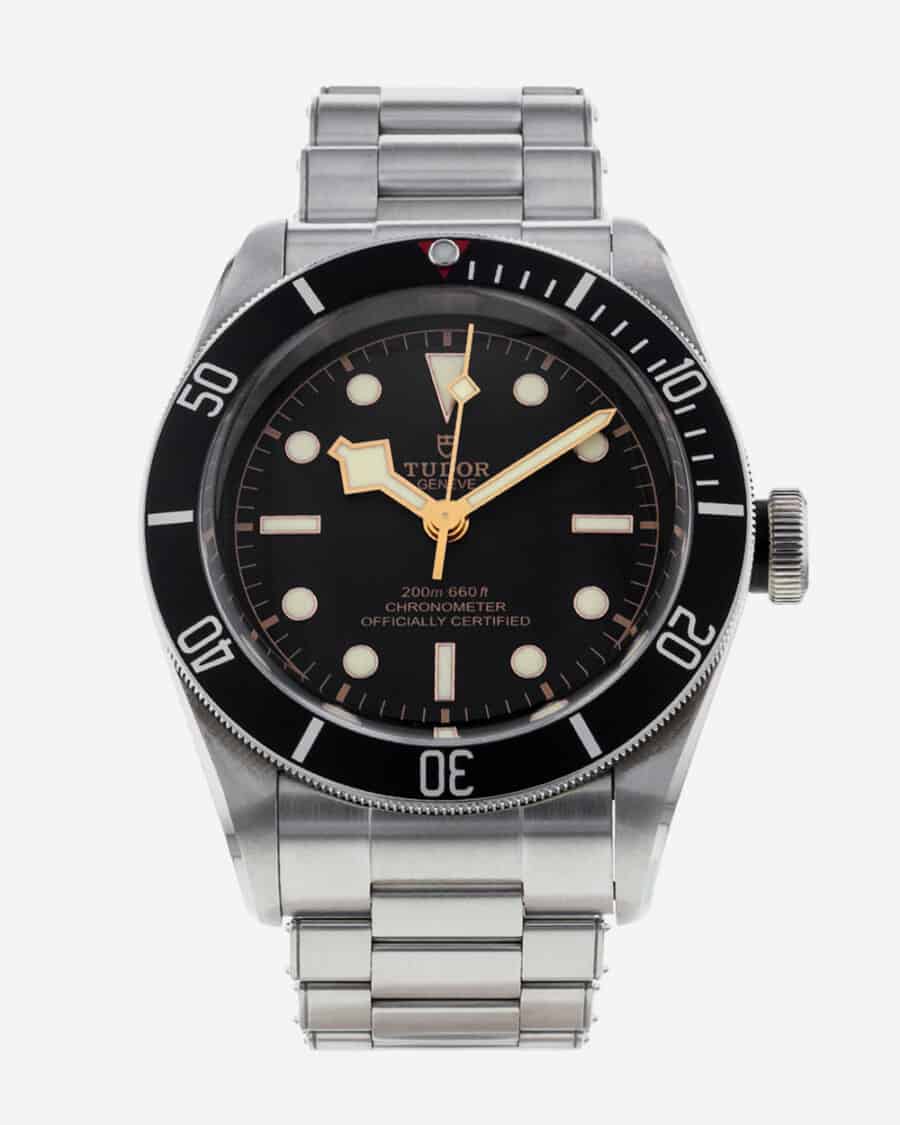

Tudor watch movements are made by Kenissi

However, Tudor says its movements are in house despite them being made by Kenissi, in which Tudor, as well as Breitling and Chanel, have a stake. And what about Oris, whose Calibre 400 is developed by its in-house team but made by an undisclosed third party? The intellectual property is very much in house, the business of making has just been outsourced.

The more reasonable argument seems to be that unless you’re paying substantial sums, surely it is better to have a tried-and-tested movement, such as an ETA 2824, which was launched in 1972 and has kept the likes of Hamilton, Tudor and TAG Heuer ticking, powering your timepiece rather than a new untested movement.

Using the term ‘in house’ is, for some marques, a clever marketing tool to appeal to watch snobs, for others it’s a badge of honour – you need to have a dig around once you’ve found the brand you like to find out the details. Whether it matters personally when buying a watch is all down to preference.

Key third-party watch movement makers

A Tissot with a Valjoux 7750 movement

Not all brands have the capacity or the budget to make their own movements, so they rely on a third-party supplier. One such name is the aforementioned ETA, which, in a legal twist no one saw coming, now wants to go back to supplying third parties – but only if it can choose them.

The classic ETA is the 2824. It has been manufactured since 1982 and is generally considered to be the industry’s workhorse – robust, reliable and easy to repair. The next ETA to know is the more refined 2892. This is the choice for those brands who can’t manufacture their own movements but want to have a base calibre to play with, adding complications such as chronographs. It is also thinner so can be used in dress styles.

If you’re a brand looking for an integrated chronograph – where the timing module is part of the movement, not added on – then it’s the Valjoux 7750. First made in 1974 by the now-Swatch Group owned Valjoux, it was specifically designed to be mass produced, and highly accurate. It’s now an industry icon. TAG Heuer has used it in the past, as has Omega, and it has provided a base for higher-price point brands such as IWC.

Also from Switzerland is Sellita. Sellita used to assemble 2824s until ETA decided it didn’t want to send out unconstructed movement kits, so Sellita responded by creating a base calibre, the SW200, that was almost identical to the 2824, and just as good. Montblanc, IWC, and Oris all use original, as well as heavily modified, versions of Sellita’s calibres.

Christopher Ward’s C65 model is powered by a Sellita SW200 movement

The third Swiss name is Soprod. Owned by the Festina Group, which largely makes fashion watches, it is mainly used by Sinn and Seinhart.

Head East and the movement landscape is dominated by Seiko and Citizen. A timepiece with one of these movements are likely to be cheaper than Swiss watches – not because of any quality issues but because they will have been assembled on an automated robotics line rather than by hand, which keeps costs down.

You also have Seagull and Shanghai Watch Industry Corps in China, used by the likes of Ingersoll and Stuhrling. It’s worth mentioning that Grand Seiko is making movements with finish, beauty and accuracy to rival any Swiss manufacturer, and it’s still a rather under the radar watchmaker, should you wish to stand out from the Swiss-dominated crowd.

Swiss made vs the world

Audemars Piaget’s Musée Atelier in Le Brassus, Switzerland

Swiss made is probably one of the most international recognised signifiers of quality. However, it isn’t just a stamp applied to the output any watch brand with a Jura postcode; it is, in fact, a legal stricture. To use those two words, 60% of the manufacturing costs of a watch must be generated in Switzerland. In addition, the movement must also be considered Swiss, which means encased in Switzerland and with final inspections of the watches done there also.

Even though it is an open secret that many brands get their parts from China, they can still fulfil this legal requirement as costs there are lower. Therefore, they don’t make up as much of a percentage of the manufacturing costs compared to what is done in Switzerland.

The Swiss, although not the originators of the watch industry (that honour goes to the Germans), have dominated it since the 1800s, apart from a brief blip in the 1970s, when the Japanese flooded the market with quartz and nearly destroyed the Swiss watchmaking industry in the process. That most of the industry renowned names are based in Switzerland and are also the companies with the greatest size and output has only added to its dominance of the industry, and the sense that the only watch worth having is a Swiss one.

Yet there are challengers to the Swiss crown. Germany in general, and Glashutte in particular, is home to the likes of Nomos and Lange & Sohne, and is a watchmaking hub with a world-class reputation. Seiko and Citizen are flying the flag for Japan, and, with brands such as Atelier Wan and Seagull, even China is sloughing off its reputation as the land of cheap fakes.

While ‘Swiss made’ will always be a mark of quality, as the reach of the watch industry grows Switzerland is no longer the only place to turn for well-made watches. With the likes of Bremont, Fears, Christopher Ward and Farer, even the UK is starting to get a look in.

Modern mechanical watches

Patek Philippe Aquanaut watch

Just because a mechanical movement is anachronistic doesn’t mean it hasn’t been upgraded since the 17th century. Ulysse Nardin was the first brand to use silicon – a material that is lighter and harder that steel, but more importantly resistant to magnetism, corrosion and shock and needs no lubrication – in 2001 in the escapement of its revolutionary Freak.

It was quickly adopted by even the most traditional of watch houses, including Patek Philippe which went on to develop a proprietary silicon called Silinvar. It even experimented with compliant technology for its 2017 Travel Time Advanced Research Aquanaut, which replaced the usual cogs and pinions needed for a travel-time function with a single piece of flexible steel.

Zenith El Primero

Another brand keen on finding single elegant replacements for multiple wheels and gears is Zenith. In 2017 it unveiled its Defy Lab, which had a single-piece oscillator distributing power, as opposed to the traditional ‘spring balance’. Then it turned its attention to high frequencies and, after five years of R&D, launched the El Primero 3600 – a revamp of 1969’s headline-grabbing integrated automatic chronograph but this time with the ability to measure 1/10th of a second.

Not wanting to be left out, the Swatch Group partnered with Audemars Piguet to launch a hairspring made from Nivachron – a titanium alloy that is anti-magnetic like silicon but produced using the same process as nickel-steel springs. In 2019, it was placed in a limited-edition Swatch. Now you can buy the technology in a $XXX/£695 Certina.

The co-axial escapement is now at the heart of every Omega watch

Then there’s the most important evolution since a handful of brands worked out how to make a chronograph automatic and integrated in 1969 – the co-axial escapement. Invented by British watchmaker George Daniels, it replaced the lever escapement (an escapement construction where the wheel is moved on by a rocking lever which bifurcates with two pallets at either end). This construction hadn’t been improved upon since the 18th century when it was invented fellow Englishman Thomas Mudge.

In the co-axial, rather than use sliding friction, a wheel is added to the lever, which is now split into three forks with pallets at the end, allowing the escapement to use radial friction. This removes the need for lubrication, reduces abrasive friction and ensures greater accuracy over time. Daniels patented this invention in 1980 and spent the intervening 19 years trying to interest larger brands to commercialise it. In 1999, Omega finally listened, worked out how to mass produce it, and it’s now at the heart of every Omega movement.

5 mechanical watches for every budget

You’ve been sold on a mechanical watch, but what to purchase? Here’s five of the best.

The budget option: Seiko 5

An icon for less than the price of a Michelin star tasting menu.

The chronograph: Tissot Heritage 1973

You could opt for one of the 1969’ers – a Calibre 11 or an El Primero – but for most watch enthusiasts it’s all about the Valjoux 7750. And this Tissot is the best case for it.

The workhorse: 2015 Black Bay

New Tudors have in-house movements. But you can purchase this with an ETA 2824 powering it. Yes, you could buy an ETA cheaper, but this gives you two icons at one price.

The in-house: Zenith Defy Revival A3691

Zenith could make a lot more watches than it does. However, that would compromise the desire to keep things as in house as possible.

The manual wind: Grand Seiko Manual Winding 1960 Re-Creation

Elegant, refined, and not Swiss. This classic three-hander is the ideal reminder of why a manual wind is the perfect daily companion.